Burroughs as Muse and Collaborator: Inspiring Musicians from Joy Division to Iggy Pop to Nirvana

William S. Burroughs was, according to director John Waters, “the first person who became famous for things you were supposed to hide.” Burroughs' heroin addiction is almost synonymous with his name. He wrote about drugs and the underside of society. He showed no remorse nor attempted any justification for his actions. Burroughs has been referred to as "Gentleman Outlaw," "Pope of Dope," and a "junkie." He brought the technique of cut up writing to a wider audience and inspired David Bowie, Kurt Cobain of Nirvana, and Thom Yorke of Radiohead to experiment with it in their music. Lou Reed cites Burroughs as “the person who broke the door down. When I read Burroughs, it changed my vision of what you could write about, how you could write.” Burroughs allowed people to write about their indiscretions; his postmodern approach to literature introduced a new way to read and write. His writing created a new audience for publishers that had never existed before: those interested in style and form and uninterested in moral tales.

Why did Burroughs appeal to these musicians more than the other Beat writers? Burroughs came from a good home. He came from money. He attended Harvard University. He should have been an insider. But he was an outsider. His writing, while respected, was the most dark of the Beat Generation. His first book, Junkie, was about being a heroin addict. He was obsessed with guns. He accidentally shot his wife in an intoxicated game of William Tell. Burroughs appears to be the outsider even within the Beats. He never visits the others in On The Road; they all visit him. They have to leave society to be amongst his company.

Burroughs' musical influence and admiration spans decades and different genres. He is the only Beat writer on The Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club album art. Joy Division named one of their songs, "Interzone," after the metaphorical stateless city Burroughs created. In Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” Pop sings “Here comes Johnny Yen again with the liquor and drugs” and later sings “something called love, yeah, that's like hypnotizing chickens.” Both are references to Burroughs' writing. Music references later turn to musical collaboration. He recorded excerpts from his books and short stories that were set to music by Sonic Youth, John Cale and others, called Dead City Radio. Burroughs did a cover of R.E.M.’s "Star me Kitten," with the band. He read from his books while hip hop duo, The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, set the reading to music, creating an entire album.

Al Jourgenson, of the industrial band Ministry which rose to popularity in the nineties, looked to Burroughs (and Timothy Leary, psychologist and psychedelic drug advocate) as father figures. Jourgenson admitted to being an addict and wrote "Just One Fix" about heroin addiction and withdrawal. Burroughs first appears in the video wearing a full suit and hat, saying "Break it all down." Interspersed through the video are two young men, one of them going through withdrawal. They check into a flophouse and we watch the boy as his body breaks down fiending for just one more fix. The band plays loud and fast. Burroughs reappears in the video, wearing jeans, a button down shirt and a tie. Instead of shooting heroin, Burroughs shoots clay plates with his gun. The plates read, "reality" "control" "history" "image" "language" "society." This song and video which appear to warn off people from heroin addiction presents an intentionally mixed message by featuring the most infamous junkie of all time, who lives another five years. Ministry also released a single called “Quick Fix” with Burroughs reading over their music.

Later that same year (1993), Kurt Cobain of Nirvana collaborated with Burroughs on a song, all of which was completed by mail, "The 'Priest' They Called Him." Burroughs sent Cobain a recording of him reading the poem and Cobain recorded music to the reading and sent this back to Burroughs. This song is about a priest addicted to heroin and how he gives his last fix to a young man in pain. Because of his good deed, the priest dies, and he is released of his suffering. With this recording, Kurt Cobain introduced a whole new generation to Burroughs. The music stays true to Burroughs’ writing and themes. Discord and guitar feedback accentuate the dying priest’s desperation and addiction.

Maybe he appeals to underground musicians* because the other Beat writers focused on life and acceleration and represented the energetic spirit of America while Burroughs represented the underbelly of society. He lived in a swamp, he shot his wife, he was a self-professed junkie. Even the way they read poetry reflected their lives. Ginsberg read with animation, with a quick cadence. Kerouac read with an influence of jazz and bop, fast, movement, clean words ending efficiently. Cassady, as we know from Kerouac, did everything with an immediacy, he was the spirit of speed, passion personified. But Burroughs, he slurred his words, he said each word with effort, and slowly one word melds into another. Long silent breaks marked commas or the end of sentences.

Music references abound relating to Burroughs’ influence, inspiration, and admiration in music. There are too many to list, so I’ve kept to music I own and listen to. Just this year, Chelsea Light Moving, a new band featuring Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, released an album with what they termed “Burroughs rock.” Although the gentleman outlaw has been dead sixteen years, his writing is still relevant. His writing and reading still inspire other people to create art.

The other Beat writers were associated with life while Burroughs was associated with death. A slow, long, addictive death. But he outlived Kerouac, Cassady, and Ginsberg. His writing was more experimental than the others and harder to decipher. He challenged his readers in ways his peers never did.

*I use the term underground loosely here. While most of the musicians mentioned in this piece rose to mainstream popularity, their roots began in the punk, gothic, industrial, and indie scenes.

References

William S. Burroughs, Junkie. New York: Grove Press, 2003.

William S. Burroughs and Joy Division, Reality Studio, 2008.

John Dineen, William S. Burroughs - The Source, Bearded Magazine, 2011.

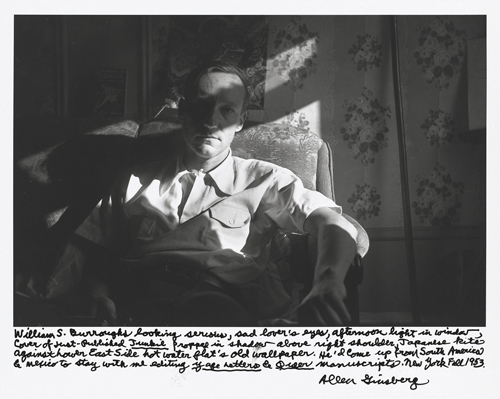

Image: Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs looking serious, sad lover’s eyes..., 1953. Gelatin silver print, printed 1984–1997, 7 9/16 x 11 7/16 in. National Gallery of Art, Gift of Gary S. Davis. Copyright © 2013 The Allen Ginsberg LLC. All rights reserved. Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg. On view May 23–September 8, 2012. Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

About the Author

Melanie Samay studied literature at Fordham University in New York and received her Masters in English literature from San Francisco State University. Currently she works in marketing for the Contemporary Jewish Museum. She spends her time reading, walking around the city, sitting in the park with friends, and hanging around dark spaces at night listening to loud music. Read more from Melanie on her blog about books and book-nerdom: http://soifollowjulian.com

Why did Burroughs appeal to these musicians more than the other Beat writers? Burroughs came from a good home. He came from money. He attended Harvard University. He should have been an insider. But he was an outsider. His writing, while respected, was the most dark of the Beat Generation. His first book, Junkie, was about being a heroin addict. He was obsessed with guns. He accidentally shot his wife in an intoxicated game of William Tell. Burroughs appears to be the outsider even within the Beats. He never visits the others in On The Road; they all visit him. They have to leave society to be amongst his company.

Burroughs' musical influence and admiration spans decades and different genres. He is the only Beat writer on The Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club album art. Joy Division named one of their songs, "Interzone," after the metaphorical stateless city Burroughs created. In Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” Pop sings “Here comes Johnny Yen again with the liquor and drugs” and later sings “something called love, yeah, that's like hypnotizing chickens.” Both are references to Burroughs' writing. Music references later turn to musical collaboration. He recorded excerpts from his books and short stories that were set to music by Sonic Youth, John Cale and others, called Dead City Radio. Burroughs did a cover of R.E.M.’s "Star me Kitten," with the band. He read from his books while hip hop duo, The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, set the reading to music, creating an entire album.

Al Jourgenson, of the industrial band Ministry which rose to popularity in the nineties, looked to Burroughs (and Timothy Leary, psychologist and psychedelic drug advocate) as father figures. Jourgenson admitted to being an addict and wrote "Just One Fix" about heroin addiction and withdrawal. Burroughs first appears in the video wearing a full suit and hat, saying "Break it all down." Interspersed through the video are two young men, one of them going through withdrawal. They check into a flophouse and we watch the boy as his body breaks down fiending for just one more fix. The band plays loud and fast. Burroughs reappears in the video, wearing jeans, a button down shirt and a tie. Instead of shooting heroin, Burroughs shoots clay plates with his gun. The plates read, "reality" "control" "history" "image" "language" "society." This song and video which appear to warn off people from heroin addiction presents an intentionally mixed message by featuring the most infamous junkie of all time, who lives another five years. Ministry also released a single called “Quick Fix” with Burroughs reading over their music.

Later that same year (1993), Kurt Cobain of Nirvana collaborated with Burroughs on a song, all of which was completed by mail, "The 'Priest' They Called Him." Burroughs sent Cobain a recording of him reading the poem and Cobain recorded music to the reading and sent this back to Burroughs. This song is about a priest addicted to heroin and how he gives his last fix to a young man in pain. Because of his good deed, the priest dies, and he is released of his suffering. With this recording, Kurt Cobain introduced a whole new generation to Burroughs. The music stays true to Burroughs’ writing and themes. Discord and guitar feedback accentuate the dying priest’s desperation and addiction.

Maybe he appeals to underground musicians* because the other Beat writers focused on life and acceleration and represented the energetic spirit of America while Burroughs represented the underbelly of society. He lived in a swamp, he shot his wife, he was a self-professed junkie. Even the way they read poetry reflected their lives. Ginsberg read with animation, with a quick cadence. Kerouac read with an influence of jazz and bop, fast, movement, clean words ending efficiently. Cassady, as we know from Kerouac, did everything with an immediacy, he was the spirit of speed, passion personified. But Burroughs, he slurred his words, he said each word with effort, and slowly one word melds into another. Long silent breaks marked commas or the end of sentences.

Music references abound relating to Burroughs’ influence, inspiration, and admiration in music. There are too many to list, so I’ve kept to music I own and listen to. Just this year, Chelsea Light Moving, a new band featuring Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, released an album with what they termed “Burroughs rock.” Although the gentleman outlaw has been dead sixteen years, his writing is still relevant. His writing and reading still inspire other people to create art.

The other Beat writers were associated with life while Burroughs was associated with death. A slow, long, addictive death. But he outlived Kerouac, Cassady, and Ginsberg. His writing was more experimental than the others and harder to decipher. He challenged his readers in ways his peers never did.

*I use the term underground loosely here. While most of the musicians mentioned in this piece rose to mainstream popularity, their roots began in the punk, gothic, industrial, and indie scenes.

References

William S. Burroughs, Junkie. New York: Grove Press, 2003.

William S. Burroughs and Joy Division, Reality Studio, 2008.

John Dineen, William S. Burroughs - The Source, Bearded Magazine, 2011.

Image: Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs looking serious, sad lover’s eyes..., 1953. Gelatin silver print, printed 1984–1997, 7 9/16 x 11 7/16 in. National Gallery of Art, Gift of Gary S. Davis. Copyright © 2013 The Allen Ginsberg LLC. All rights reserved. Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg. On view May 23–September 8, 2012. Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

About the Author

Melanie Samay studied literature at Fordham University in New York and received her Masters in English literature from San Francisco State University. Currently she works in marketing for the Contemporary Jewish Museum. She spends her time reading, walking around the city, sitting in the park with friends, and hanging around dark spaces at night listening to loud music. Read more from Melanie on her blog about books and book-nerdom: http://soifollowjulian.com

Comments